Island Heritage

Gigha’s People

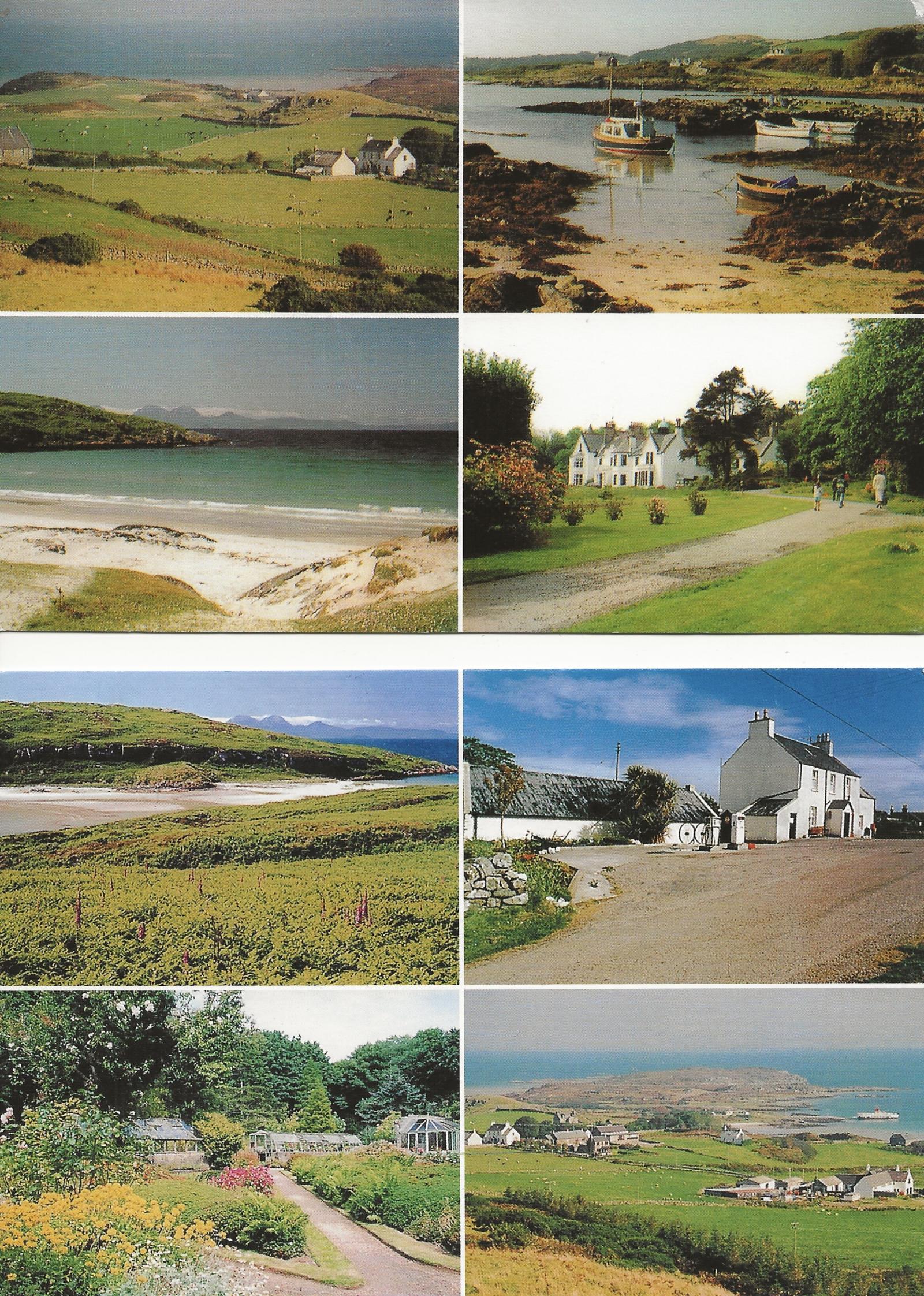

Island life might seem quiet these days but the seas around the Hebrides were once a highway, with Gigha at a crossroads. Nearly 2,000 years ago, Irish settlers brought their culture and language to this area, creating the first Gaelic-speaking kingdom in Scotland. Gaelic was still the first language of Gigha for a large part of the 20th century.

OWNING GIGHA

In the 9th century the Norse took control, ruling Gigha and other Hebridean islands for nearly 400 years. Their final chapter was written here when King Haakon IV’s huge fleet of ships gathered off Gigha in 1263 before their defeat at the Battle of Largs. For centuries thereafter rival clans fought to control the islands but on Gigha the MacNeills ultimately prevailed. In 1865, they sold the island to a private owner, James Scarlett, and until 2002 it was bought and sold by a series of landlords, each bringing their own ideas about how Gigha should be managed.

CHANGING LAND

Looking at the fields and farms on our island, it is easy to assume that little has changed. But across the island, you can see the signs of old ways of managing the land. Look out for grass-covered lines of stones marking the boundaries of ancient fields and buildings. In the 1950s, Gigha had thirteen farms and eight crofts, all supplying milk to the island’s creameries for cheese production. Since then, hard-working Clydesdale horses have been replaced by tractors and other farm machinery and now there are just four working farms. The creameries have gone but island produce has diversified and at times has included milk, ice cream, oysters, farmed halibut and salmon. Everything and everyone arrives on Gigha by sea. Before the first steamships started passing by in 1877, people took rowing or sailing boats on the three-mile crossing to the mainland. For a further eighteen years ferrymen still rowed passengers from ship to shore, until 1895 when Gigha got its first pier. Since 1979, a car ferry has carried people off the island for work and today, children can get to secondary school on the mainland every day and be home for tea – as long as the weather is fair.

BUYING GIGHA

In 2002, the community took the extraordinary step of buying Gigha from the last private landlord. With the help of the Scottish Government and a huge fundraising effort, the islanders took ownership, and the Isle of Gigha Heritage Trust was set up to manage the island on their behalf. At the time, just 92 people lived here. Twenty years later the population had doubled, bringing new businesses and ways of life - from farming and aquaculture to crafts, retail and tourism. Our wind turbines, known as the Dancing Ladies, generate green energy and income for the island.

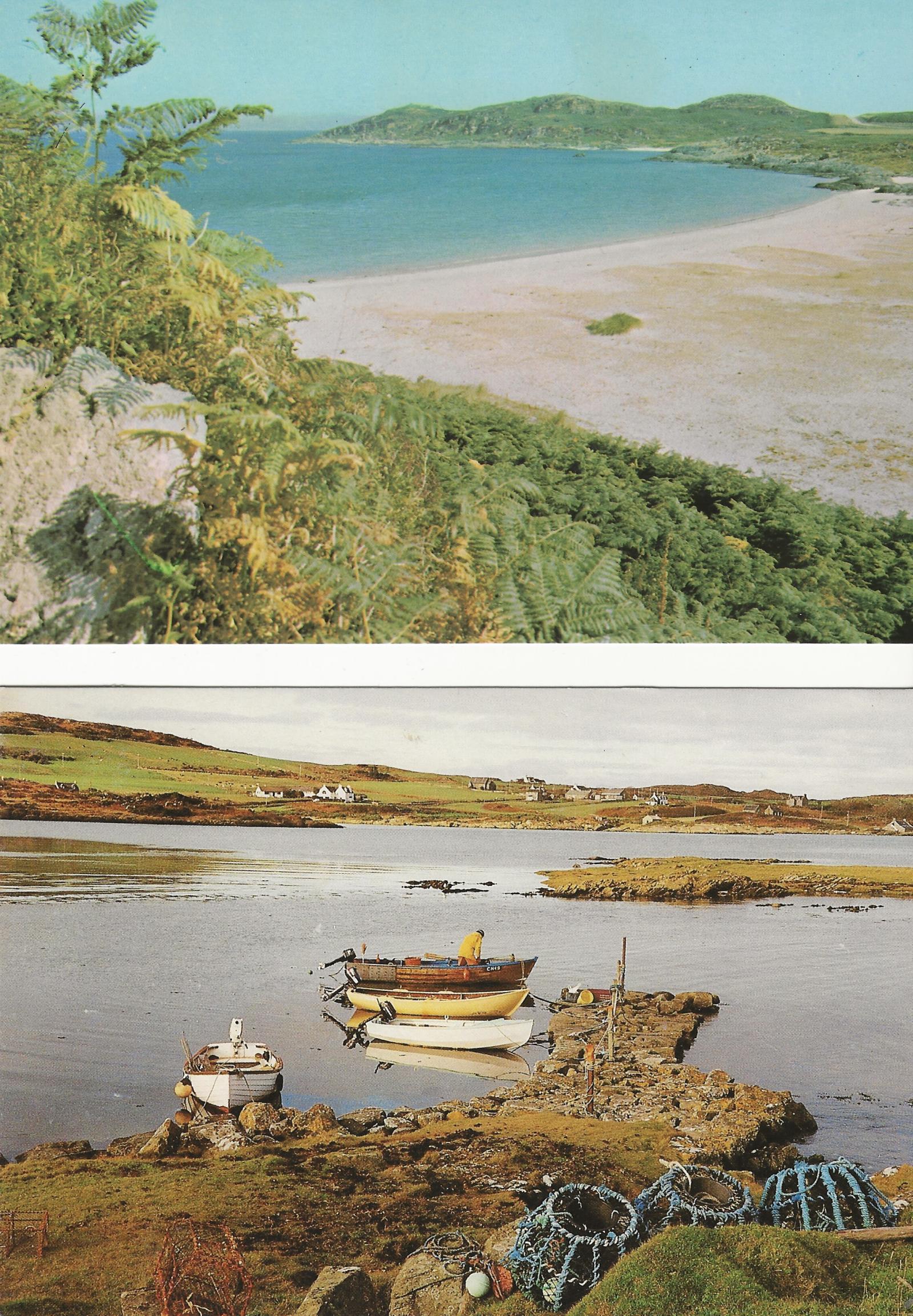

The west

WATERMILL, PORT AN DÙIN - Port of the Fort

In the 19th century, islanders brought their oats to Ardailly for grinding in the watermill down to the left of the bay. Water was collected in the Mill Loch, channelled down the lade to the mill and then out to the sea. The heavy cast-iron waterwheel came here by boat to avoid a difficult journey across the island. Here, the rhythmic sound of the turning wheel and splashing water was a backdrop to everyday life. A trip to the mill was part of each year’s cycle of growing, harvesting and storing food. A good crop of oats kept every family going especially in the long dark winter months.

THE CHANGING WEST

Like every part of the Highlands and Islands, Gigha has seen a huge drop in the number of people living permanently on the island. Around 250 years ago, there were 600 islanders – now there are fewer than 200. The west of the island was probably Gigha’s main settlement and there are signs of long-abandoned homes and walls built to create fields and animal enclosures. It is said that at one time the smoke from at least 12 chimneys could be seen from the mill. The west was particularly affected as people left to find work and a new life on the mainland, overseas, or just on the more sheltered east side of the island. Some settled in Cape Fear in North Carolina. According to one account, Neill MacNeill of Ardailly brought the first Highlanders to the colony in 1739. It became the largest settlement of Highlanders outside Scotland.

Tarbert

CNOC LARGIE / HIGHFIELD HILL

We are very close to Ireland on Gigha and Irish traders have been regular visitors to our shores. Many of them clambered up the slopes of Cnoc Largie to visit a cluster of flat stones which they believed to be the grave of a king. A large block of natural rock is said to be his headstone. So many visitors came up this way that the narrow pass at the top of the hill is known as the Irishman’s Gap.

TOBAR A’ BHEATHAIG - Well o’ the Winds

Spring water has long been believed to possess healing powers and, in the past, wells like ours were looked after by a local guardian. Sailors wanting a fair wind left an offering here at the well and asked the guardian to throw its water in the direction from which they wanted the wind to blow. As far back as the late 1600s, traveller Martin Martin described people visiting the great well on Gigha, leaving tokens of money, pins or needles or even pretty stones as thanks for a healing drink.

IN THE BALANCE

In 1849 two men were preparing the ground for planting their potato crop near Tràigh Bhàn an Tairbeart (Tairbeart Bay). Finding a boulder in their way, the men moved it, revealing a buried stone box containing a set of delicate weighing scales. The finely worked bronze scales and a set of lead weights date back to the 10th century when the island was ruled by the Norse. But we don’t know exactly why and when they were left here, or why they were so carefully buried in the ground.

The South

CREIDEAMH, DÒCHAS, CARTHANNAS & CO-CHÒRDADH – THE DANCING LADIES

Faith, Hope, Charity - and Harmony

Gigha’s wind turbines are a daily reminder of our powerful ocean winds, supplying energy to the national grid. Three of the ‘Dancing Ladies’ have produced energy since January 2005. Ours was the first Scottish community-owned wind farm connected to the grid. It was a huge achievement, ensuring a steady income which is ploughed back into the island and showing other rural communities the benefits of investing in wind energy. In 2013 we added a fourth turbine - ‘Harmony’.

CALM BEFORE THE STORM

In October 1263 the sheltered waters at the south of the island were visited by a huge fleet of warships led by King Haakon of Norway in his magnificent oak ship with 37 benches for oarsmen and a dragon’s head carved into the prow. At the time, Gigha and the other Hebridean islands were ruled by Norway, but King Alexander III of Scotland wanted to take control. As tensions rose, Haakon sailed here, demanding loyalty from local rulers including Eòghan, Lord of Argyll. Alexander lured Haakon round to Largs in Ayrshire where many of the Norwegian ships were destroyed by a storm. Haakon retreated to Orkney and died that winter. Three years later, the Hebrides were ruled by the King of Scots.

OVER THE SEA TO CARA

Cara Island is just one mile long and half a mile wide. Today, no-one lives there permanently but it’s been a home to crofters, a shelter for visiting fishermen and has seen violent clashes between the MacDonalds and the Campbells during clan power struggles. It’s also home to The Broonie, a household sprite with the power to help or cause trouble depending on his changing moods! Householders could wake up to find the housework mysteriously done or return to the island to discover their cows had been milked. But the Broonie had the power to whip up a storm or land a punch with his invisible fist. If you visit Cara, be sure to remove your hat and wish him a good day to avoid trouble!

GALLOCHOILLE

Back in the late 1800s, islanders waited here for ferryman Willie Orr and his large wooden rowing skiff to convey them to Tayinloan or to the mail steamer Glencoe on its way to Islay. On bad days people took shelter under an upturned boat - big enough to have a door, seats, a stove and a chimney. Willie carried up to a dozen people in all weathers, his strong arms working the heavy oars. Out of the shelter’s warmth, the passengers often got soaked, ending their journey with an awkward clamber onto a larger vessel or the mainland shore. Today all that remains are the metal rings that once supported the ferry signal pole.

CUDDYPORT

Gigha has a gentle climate where potatoes grow well in the sandy coastal soil. Irish traders sailed to Cuddyport during and after the Irish famine, visiting the storage shed to buy seed potatoes – the remains of potato scales have been found here. It’s said that back home they placed the best of the Gigha crop at the top of their sacks to attract buyers.

If you look at the rocky promontory on the left of Cuddyport bay, at the far end there’s an array of circular markings carved into the stone. This is a quarry for quern stones, used for grinding oats and barley. Two stones were needed, one turning on top of the other. Half-made quern stones are still embedded in the rock, long awaiting their turn for removal.

SLOC AN LEIM

At the Spouting Cave, with the right combination of tide and wind, the waves spurt high up out of a cleft in the rock. But it can be dangerous, especially at high tide. Take very good care as the rocks are slippery, the water can be wild, and the blowhole is quite hidden. Nearby, the small hill of Càrn an Lèim gives views to Kintyre to the left, Islay to the right and, on a clear day, Ireland not far to the south.