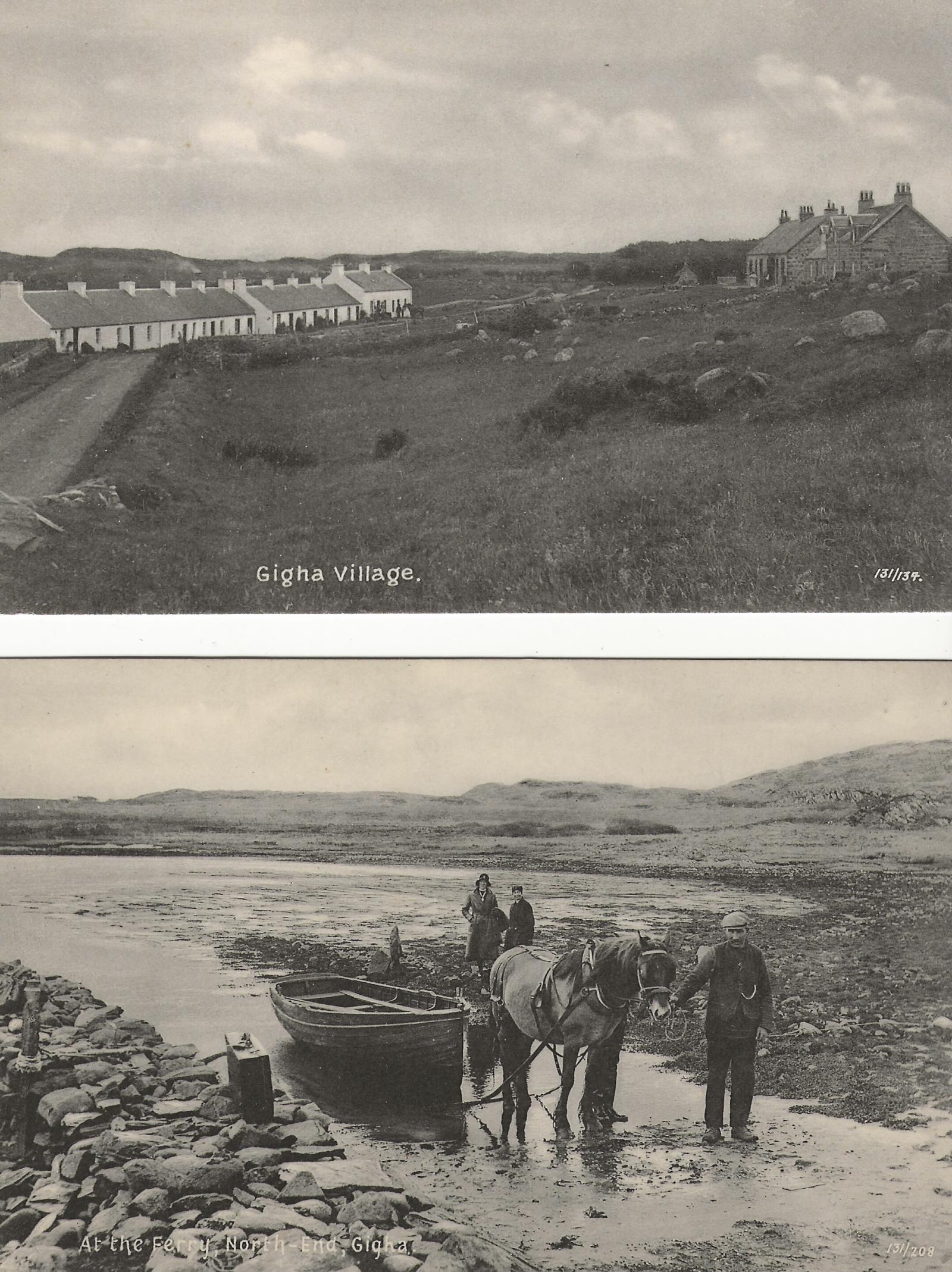

gigha's historic sites

BODACH & CAILLEACH

At noon and night these stones are said to walk the heaths of Gigha. To us they are the Bodach and Cailleach, the old man and old woman in Gaelic. The Cailleach, the smaller stone, is the goddess of wilderness and winter. They may have links to pre-Christian Ireland over 1,500 years ago - Irish sailors still placed offerings here in the 19th century. But they are not alone. Similar-shaped bodachs are found in Perthshire, while other bodachs and cailleachs are woven into Highland and Hebridean landscapes. Tradition tells us that our Bodach must always face Ireland and that it’s bad luck if he falls - so tread carefully!

BULL OF CRARO

Our landscapes tell stories and help us remember who and where we are. Looking towards to Craro Island, you might spot a rock shaped like a bull facing north-east. One story tells how the bull saved a boy’s life... Once a cabin boy was on a ship attacked by pirates. Fearing for his life, the boy prayed to God to protect his mother on Gigha. A pirate overheard him. Knowing Gigha himself, he decided to test the boy’s knowledge of the island, asking which way the bull of Craro faced. The boy answered correctly, proving he was from Gigha, and his life was spared. Worth remembering? You never know.

CAIRNVICKUIE, HOLY STONE - SM3306

Before Christianity, many people across Scotland had beliefs often rooted in the natural world. Missionaries found ways to blend pagan worship with Christian beliefs, adding crosses and other religious symbols to pagan spiritual sites, so making them part of the faith. At one time, women wanting to have a baby crawled to Tarbert to sit on a stone they believed would help them conceive. Known today as the Fertility or Holy Stone, it is marked with both pagan and Christian symbols. Ridh’ a’ Chaibeil (Field of the Chapel) was the focal point for Christian worship and a burial ground long before the chapel was built further south in Kilchattan. The upright stone in the middle of the field at Tarbert is a weathered and broken Celtic cross more than 1,000 years old.

CÀRN BAN - SM3182

Around 4000 years ago, eight or more people were buried in Càrn Ban. One was a woman, laid on one side with her legs curled up to fit into the small stone chamber. White quartz rocks and pottery urns were buried with her, perhaps because they were believed to be important in the afterlife. In 1792, four of these chambers or cists were uncovered by local people as they took the stone away to build dykes, but when they opened them, they were hit with an intolerable stench that gave them violent headaches.

CÀRN NA FAIRE - WATCH CAIRN - SM3181

In ancient times, the dead were buried in a cairn on this high vantage point. Islanders lit fires to send signals to passing vessels or kept lookout for friends or foes arriving by water. In 1615, on low ground to the south, the MacDonalds and Campbells of Calder clashed over ownership of the island, leaving behind a cannon ball and flints. Now the waters carry ferries to Islay and beyond.

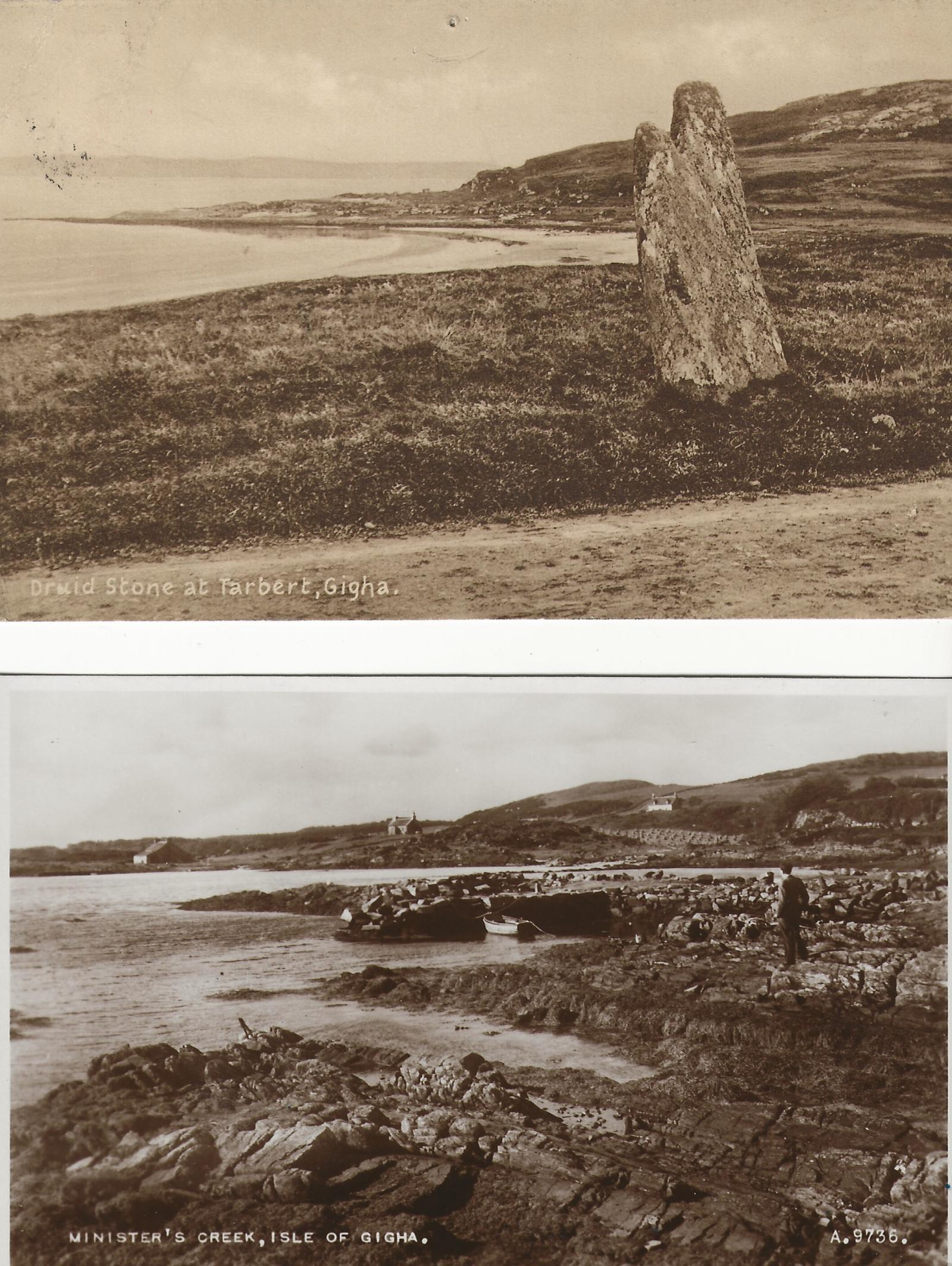

CARRAGH AN TAIRBEIRT - SM190

Since the Bronze Age or earlier, Carragh an Tairbeirt standing stone has marked the narrowest point of Gigha, tall enough to be seen from the sea from both east and west. The name might be familiar – there are several places named Tarbert (An Tairbeart or Tairbeirt in Gaelic) across Scotland, on narrow necks of land where boats could be drawn or carried from water to water. The stone marks this isthmus, but it’s likely to have had deeper meaning. Was its placement linked to cycles of the Moon or to the midsummer sunset?

Local legend knows it as the Giant’s Tooth, pulled and thrown by a giant with toothache. It’s also known as the Hanging Stone, where people convicted at nearby Cnoc an Eireachdais – the Hill of the Assembly – were hanged from the cleft at the top. Or perhaps you prefer the story of betrothed couples who shook hands through the gap for luck.

DÙN AN TRINNSE – FORT OF THE TRENCH - SM3229

A small group of people lived near Ardaily aroud 1,500 to 2,500 years ago during the Iron Age. They had a great vantage point from which to trade and fish and keep a watchful eye to the west. Dùn an Trinnse is just one of at least seven forts scattered along the length of Gigha. Another – Dùn Chibhich - sits on top of the little hill on the far side of Mill Loch and Dùnan an t-Seasgain sits to the left of the track leading back to Druimyeonmore.

DÙN CHIBHICH- SM3230

With its strong stone walls, built partly along the edge of a 10-metre cliff, this was perhaps Gigha’s most imposing ancient fortification. It is said to have belonged to Chibhich (or Keefie), the son of a Norse king, whose story is entwined with the Irish legend of Diarmuid and Gráinne. Gráinne was daughter to the Irish king. Escaping marriage to the aging warrior, Fionn MacCool, she fled north with her lover, Diarmuid, but on Gigha she fell for Chibhich. Diarmuid fought Chibhich, killing him, and the latter is said to be buried in a grave south of the summit.

FISHERMAN’S CAVE

Fisherman’s Cave once stood on the shoreline, waves pounding at the rock to create this dark, narrow space. But the land rose after the last Ice Age and the cave became a safe shelter, well above the high tide mark. Fishermen took refuge here during long fishing trips or in bad weather. They stored their gear and dried and salted fish on flat rocks nearby, ready to eat during the long winter months. Many took the chance to carve their initials and date of their visit into the rock – the oldest one dates to 1735. Please resist the temptation!

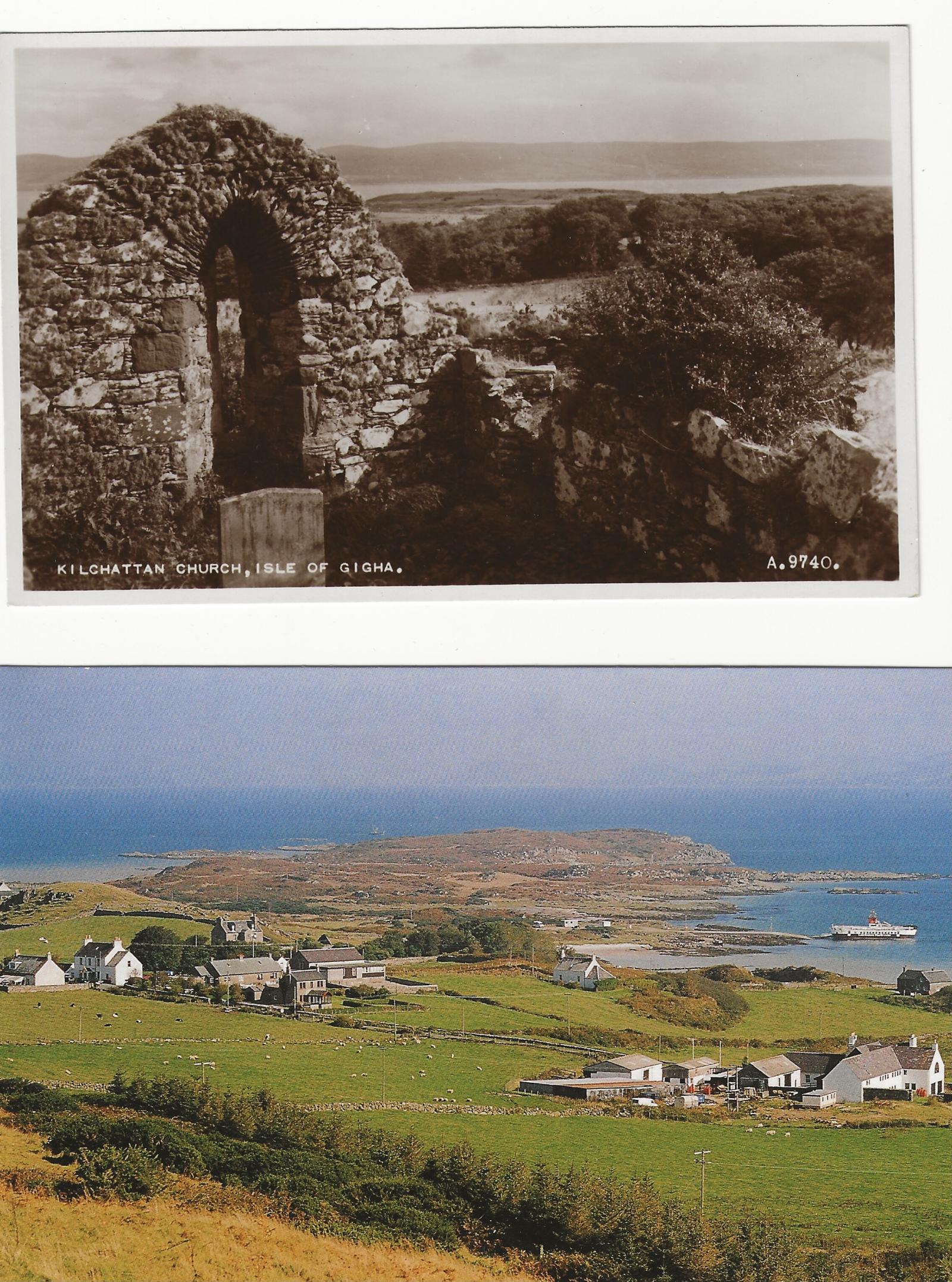

KILCHATTAN - SM3307

Kilchattan Church was built in the13th century and is dedicated to St Cathan, one of several 6th century Irish missionaries who travelled throughout the Hebrides. Standing here 500 years ago you would see richly adorned gravestones. Celtic patterns, swords, tools and animals - including an otter chasing a salmon - are still visible, the work of skilled craftsmen who sailed medieval Hebridean seas. But the carvings have faded and the men’s names have been lost – all apart from Malcolm, a 15th century chieftain, who gained Gigha when the Lord of the Isles resigned Kintyre. The stone carrying his likeness rests in the small enclosure southeast of the church. Check out our KILCHATTAN CHAPEL LEAFLET created by one of our very own island residents.

OGHAM STONE - SM259

At first glance, this stone looks plain and undecorated, but look closely and you might see groups of grooves rising vertically along the pillar’s southwest corner. Those marks are letters carefully carved in the ancient ogham script and this is one of the oldest surviving Gaelic texts in Scotland, written more than 1,400 years ago. The style of script and monument demonstrate links with Ireland. The words commemorate a man who was probably a king or chieftain based on Gigha. His name is too worn now to read, though ‘son of’ can still be made out. Only a few letters in his father’s name are now legible, but 19th and 20th century records suggest it may once have read Comginos, or Cóemgen in Gaelic, meaning ‘fair born’.